Local Geology Days 5 and 6

Notes on Geology and Topography of the Glen Feardar Area

Geology

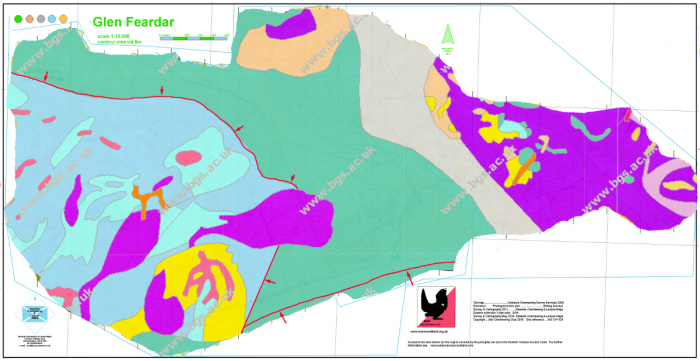

Even though the bedrock at Creag Choinich has been crushed, sheared and intruded by granite magma, it retains an overall orderliness that is far less obvious at Glen Feardar. At Creag Choinnich there is a general trend in the layering of the rock strata and the relationships between adjacent layers can be worked out – in the sense of which is older or younger than the other for instance. At Glen Feardar, only a few kilometres away, the layers of metamorphic rock have been disrupted by a more complex pattern of thrust faults and there are several different granite intrusions of varying types and dimensions. The colours on the geological map here look as if someone has been randomly splattering paint on a canvas!

Geological map of the Glen Feardar competition areas taken from the BGS Geology of Britain online viewer. Various units of Dalradian metamorphic rock have been intruded by different pulse of granite magma, shown in colours of purple, red and brown. The superimposed red lines represent thrust faults along which considerable horizontal movement occurred during the compressive phases of continental collisions over 400 million years ago.

On the west side of the map area, metamorphic schist and quartzite predominate and represent the roof of pre-existing rocks into which the granite magma rose. Some areas of granite poke through from below and can be thought of as ‘windows’ in the roof of metamorphic rock. On the east side of the map area, granite predominates on the higher ground with just a few outcrops of metamorphic rock scattered across the granite outcrop. This outcrop represents a deeper level in the granite intrusion with erosion having removed all but a few remnants of the roof of metamorphic rocks that originally capped the granite intrusion.

The thrust fault that is described at Creag Choinnich also appears here – and again lies close to the car park and arena. This time, its outcrop lies to the south and stretches along the valley to the south-west of the parking area.

One of the metamorphic rock types that outcrops in various patches within the map area is carbonate-rich rock that was originally calcareous mud and sand on the sea-bed. From the mid-18th until well into the 19th centuries, local crofters quarried this rock and roasted it in kilns that they built to extract lime that they then applied to their land. This had the benefit of greatly improving soil fertility by reducing its pH and thereby increasing the availability of nutrients to the root systems of the grass and crops on which they depended for a living.

The consequences of this simple practice were surprisingly far-reaching. The increase in fertility sustained a much larger population and, instead of generations being forced to move elsewhere to make a living, family units grew in size and the glen prospered as never before - helped in no small way by the simultaneous growth in the illegal trade of whisky distilling and smuggling. The number of ruined croft-houses and small townships scattered throughout Glen Feardar and Aberarder is astonishing and contrasts starkly with the tiny number of occupied homes today. An indication of the size of the community in the mid 1800s is that the average attendance at Aberarder school was around 30 pupils; this in a community where education would have had to take second place to the demands of the croft.

The remains of at least half-a-dozen lime kilns can still be identified within the Glen Feardar map area. Some are barely recognisable as kilns, but there is one on the slopes due north of the car park that is almost completely intact.

Intact lime kiln with a carefully constructed draw hole with stepped lintels. Peat and limestone layers were added to the bowl-shaped centre of the kiln and a fire lit in the draw hole. This started the peat burning and began the slow roasting process that probably took at least two days to complete.

If you are interested in the background to the practice of lime-burning and the social consequences in this area, visit http://www.glenbuchatheritage.com/picture/number1166.asp where an out-of-print book on the subject can be read online.

Topography

Topographically, like all the other 6-Day competition areas, there is a great deal of evidence of the erosive action of meltwater generated during, and especially at the end of, the Ice Age. Throughout the map area, there are dozens of dry channels and gullies where glacial meltwaters once thundered, either under the cover of an active ice-sheet or around the margins of a retreating one. Most of the large number of small hills and ridges that feature on this map are the remnants of bedrock that resisted the destructive erosion of these often short-lived torrents. Some of the best examples of meltwater channels gouged out of bedrock in this part of Deeside are found in the extreme NE of the Glen Feardar map. Another single large and very deep chasm slices through the hillside about 1500 metres due south of Balmoral Castle on the other side of the Dee valley.

The upper part of one of three chasms carved by melt-water into the down-valley slopes of the ridge NW of Craig Nordie at the extreme NE of the Glen Feardar map. This particular narrow gorge leads down into a surprisingly large, deeply incised feature, once full of rushing water and now littered with tumbled granite boulders.

The upper part of one of three chasms carved by melt-water into the down-valley slopes of the ridge NW of Craig Nordie at the extreme NE of the Glen Feardar map. This particular narrow gorge leads down into a surprisingly large, deeply incised feature, once full of rushing water and now littered with tumbled granite boulders.

All these channels owe their origin to the fact that the Dee Valley upstream from Balmoral is relatively constricted where two large intrusions of granite (the Lochnagar and Abergeldie granite plutons) outcrop on either side of the valley. Melting water, probably flowing under the ice of the valley glacier, encountered this obstruction and exploited at least three lines of weakness on the ridge on the north side of the valley that defines the eastern limit of the Glen Feardar (East) map.

Any note on the topographic history of Glen Feardar must mention the Muckle Spate o’ 1829. This flood was almost as big as the one at the end of 2015 that caused so much damage in Ballater and elsewhere locally. The 1829 flood was especially devastating for people living in Glen Feardar and caused much hardship. It completely overwhelmed the crofting township of Auchnagymlin, leaving behind so much sand and gravel on top of their fields that the crofting tenants here had to abandon their land. The sad remains of their homes lie just off the map’s north-west corner.

The remains of Auchnagymlin crofting township that was abandoned after it was overwhelmed by sand and gravel deposited during the ‘Muckle Spate’ of 1829. Image courtesy of http://gathering-alecfinlay.blogspot.co.uk/p/misnames.html - well worth reading!

Peter Craig, July 2017